The topic was “Longevity.” Longevity is defined as long life, or long existence or service. Amy Johnson Crow offers a writing challenge every few years called 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks. One week the topic to write about was “Longevity.”

Her prompt was to write something about the oldest person in your family tree, or maybe explore the person that took you the longest to find or maybe talk about longevity in a job or career. I hemmed & hawed on this one; I had a hard time applying the topic to any of my current genealogy projects. As I tried to determine what to write about, I thought of: who lived the longest? Who have I been researching the longest? Who is the ancestor furthest back in my tree?

Then I thought – why do I need to write about a who? Why not a what?

Maybe a piece of furniture handed down….my great aunts bureau that she inherited from her husband’s grandmother? The lace table coverings hand-crocheted by my husbands 2nd great grandmother? The oriental rug on my living room floor that has seen 5 generations of adults, kids and dogs? OR… why not write about a record source? Like the census records? Oh! there we go…I’ve got a topic….And we’re off.

The counting of a population and information about that population has been around since…well the time of Pharaohs and Romans. Romans used a list to keep track of adult men who were fit to serve in the military. The Pharaohs in Egypt had a requirement that all Egyptians report to the head of the province to be registered. Ancient China had censuses along with ancient India. I think for as long as leaders, kings, presidents have been around there has been some type of accounting of the people.

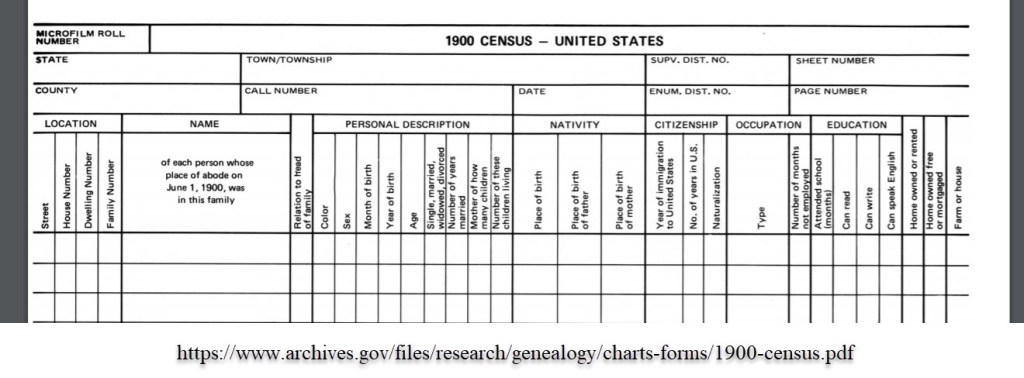

From my research, the US has been collecting data about Americans since about 1790. Family Search (a free site once you create an account) has a great collection of headings and blank forms for every census. You can find them here if you’re interested. Ancestry.com (a subscription site) also has collection of US and international census forms, along with mortality schedules, slave schedules, and veteran’s schedules (found here). The best place to learn about census records is at the National Archive web page titled Introduction to Census Records. The great thing I found in my early genealogy journey is that not only did the US collect data on a Federal Level, some states also have census records! These were usually done in the off years from the Federal census. For example, the state of Rhode Island collected census information in the years ending in 5 (1915, 1925, 1935, etc). This basically doubles the amount of information for an individual as there was some sort of census every five years.

Back in 1790 there wasn’t too much information collected. The head of families was listed with the number of free white males and females, along with the number of slaves. Women, slaves, sons and daughters did not have names recorded – they were counted only as a number. In 1820 the census records started to ask more questions, such as what type of business was someone in, if they were foreign or nationalized, if they were free colored people or slaves. The listing of each individual family member didn’t start until the 1850 census. This is the first census that asks questions of a nature that I expect a typical census to look like: age, sex, color, occupation, birthplace, marriage status, et al. Each following census collected more and different data every time.

Following families in the census records gives a genealogist, or family member, a plethora of information about their life. You can trace where a family lived in the years between census takings based on where the kids are born, you can see changing occupations, who married (or didn’t) and who took care of mom and/or dad as they got older.

The fun stuff – One family I’ve been researching is based in Rhode Island. The head of the family is Allen T., born in 1891 or 1892 to Ezra and Emily, and (so far) had one brother and two sisters.

The 1900 Federal census tells us that he’s a white male born in Sept of 1892, is 7 years old and is currently attending school. He was born in RI, his father was born in Canada (Fr.), living in the US for 30 years, since 1870 and his mother was born in VT. He’s the youngest of the 4 children, Winifred, (14), Charles (12), Ida (10) and himself. Three of his grandparents were born in Canada (Fr.), and one in Vermont. His father is a day laborer, Winifred-his oldest sister- is a spool tender, and Charles-his older brother- is a ‘back boy’. [A bit of searching shows that his occupation could be a boy working in a textile, cotton, silk or woolen mill] His father can neither read or write English, but can speak English. His mother can read and speak English, but not write it. Some interesting facts I get from this record is that no one in the family can write English, and only his mother and older sister, Winifred can read. Also noting that everyone who can physically work is working – in some sort of mill job- the assumption is this is not a well-off family, but a family of the working class.

We lose Allen T for a few years, as he is not in the 1910 census, and then pick him back up in the 1915 Rhode Island census. Allen is now 23 years old, still living with his parents. Emily is 49, and Ezra is 67. Allen T is working as a blacksmith in a shop, his father is a general mason. Neither work for themselves. The interesting fact from this census is that the birthplace of Ezra’s father has changed from Canada (Fr.) to US. In looking at a timeline of border changes between US and Canada, there is a change in the border in Passamaquoddy Bay in August of 1910 that could be the cause of his father’s birthplace changing.

In 1920 Allen T is now married with one infant daughter named Winifred. He’s 28 years old, his wife Anna is 31. Anna was born in Connecticut, and both her parents were born in Ireland. The little family is living on Willett Ave, there is no house number listed, only an X. We could assume they are living with another family, the Kennedy’s at number 52. Allen is a mechanic at an oil company earning a wage (hourly paid), William Kennedy – head of the family at #52 – is a supervisor at an oil company.

In 1925 Allen is still living on Willett Ave, the house number is listed as “no number”. The people living at #52 are now named Gardner, not Kennedy. Based on this, I’m thinking they did not live with the Kennedy’s, merely next to them. Allen is 33 now and Anna is 35, their family has grown to include Allan J (5) and John H (3.5 years), Winifred is now 6.

In 1930, the family has moved to 177 Willett Ave, with no new children. All the children are living at home with the parents. Allen now owns his home (valued at $1,000), is working as a mechanic at a garage for another person, and is not a veteran of any wars. Interestingly enough, the birthplace of Allen’s father’s is now listed as Vermont. I was not able to find any border changes during this time.

Five years after, in 1935, Annie and her sons, Allen J and John along with Winifred are all still living at 177 Willett Ave. Allen T is not listed in the state census. He is also not listed in the 1940 Federal Census. We can only assume he passed away between 1930 and 1935.

Census records, whether they be state or federal, are the records of time; they are a snapshot of a moment when a stranger knocks on the door, asks questions, and writes what he/she hears as the answer.

The answers on census schedules are only as accurate as the person being questioned – sometimes the head of the household, sometimes [against specific directions] a neighbor answering for a family not at home – OR -only as accurate as what is heard by the census taker – for example sometimes the German name Diehm is written as Deem, or Deam, or Dean.

Census schedule records provide valuable information of not only what is recorded on the page, but also what is being asked. The questions asked give us an insight as to what was important to record about the population in that particular year. In tracing Allen’s life we see the census asking ‘who can read, write, speak’ English, to the later census records having no mention of this information, but asking instead when someone immigrated, or when they became a US citizen. These snips-in-time record of our lives are the instrument by which future generations can learn about us and what people thought was important to record.

What does longevity mean to you?

It is a hard question to answer if you’ve never thought about it.

How would you apply your definition of longevity to something in your life?